What has changed in the IP over the last 50 years? - The accelerated synchronization of the world

Intellectual property

The intellectual property (IP) firm Inventa completed 50 years. With regard to this celebration, we set out to observe what has changed in the IP in the last five decades. Intellectual property is a field of the legal system that regulates the use of intellectual assets. IP rules provide that various intellectual assets may be subject to intellectual property rights. Artistic work can be the object of copyright, a mark can be the object of a trademark right, an invention can be the object of a patent right and the design of a product can be the object of design rights. These rights essentially consist in the holder being able to use those assets exclusively, for a period of time.

The legal system regulates almost all situations with legal relevance. However, as situations evolve, the legal system sometimes needs to adapt. The world has changed a lot in the last 50 years, so the legal system and, in particular, IP rules, have also changed.

Globalization and the evolution of supranational IP rules

Globalization and international trade have intensified. This fact collided with one of the IP principles, which is territoriality. In almost every country, IP rights are territorial. This means, for example, that a patent granted for an invention in a certain country gives its holder a right to exclusively use that invention only in that country. If that holder is interested in marketing the product with exclusivity in other countries, a patent will have to be obtained in each of those other countries. It is evident that this principle of territoriality, which still exists, is an obstacle to the internationalization of protection. So were the differences in national legislation. Consequently, international treaties emerged with the purpose of facilitating internationalization and bringing national legislation closer together.

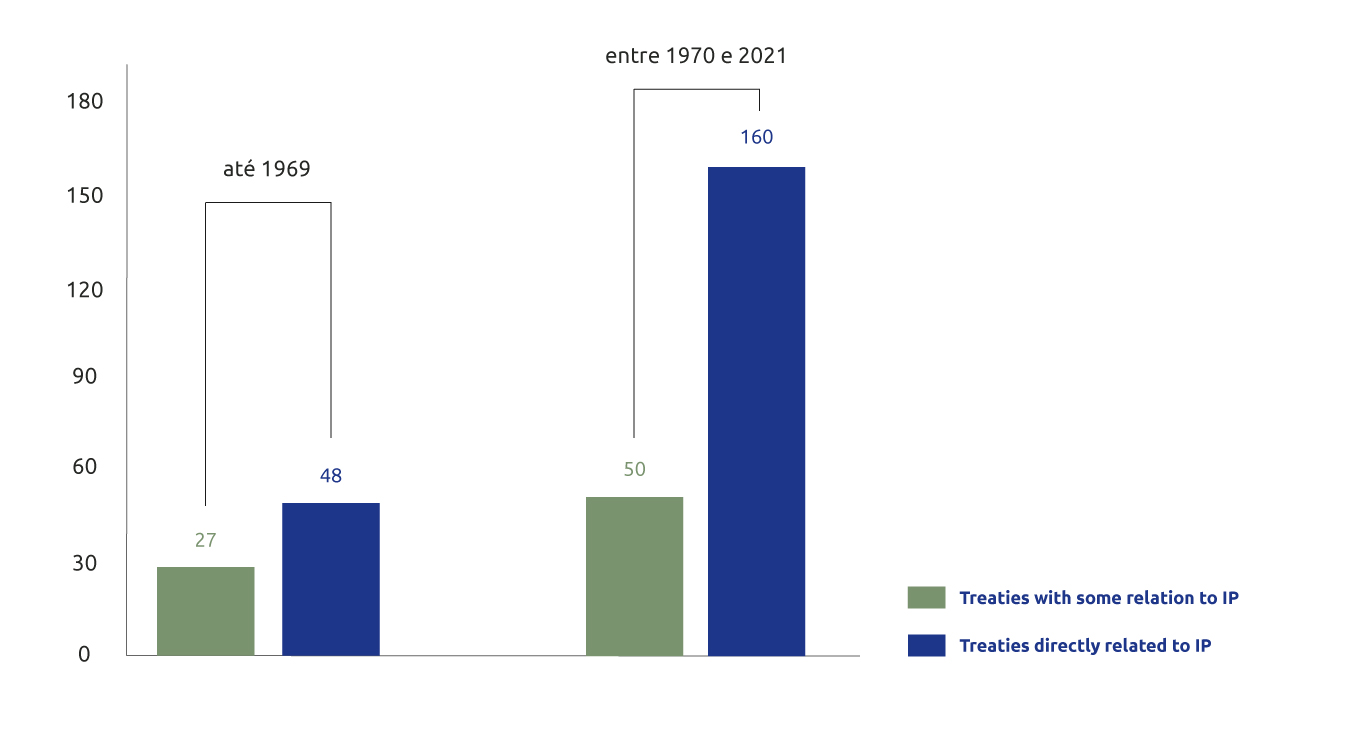

According to the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) database, there are 208 international treaties that regulate matters related to IP. Of these 208 treaties, 48 were adopted before 1970, and the remaining 160 were adopted after that date.

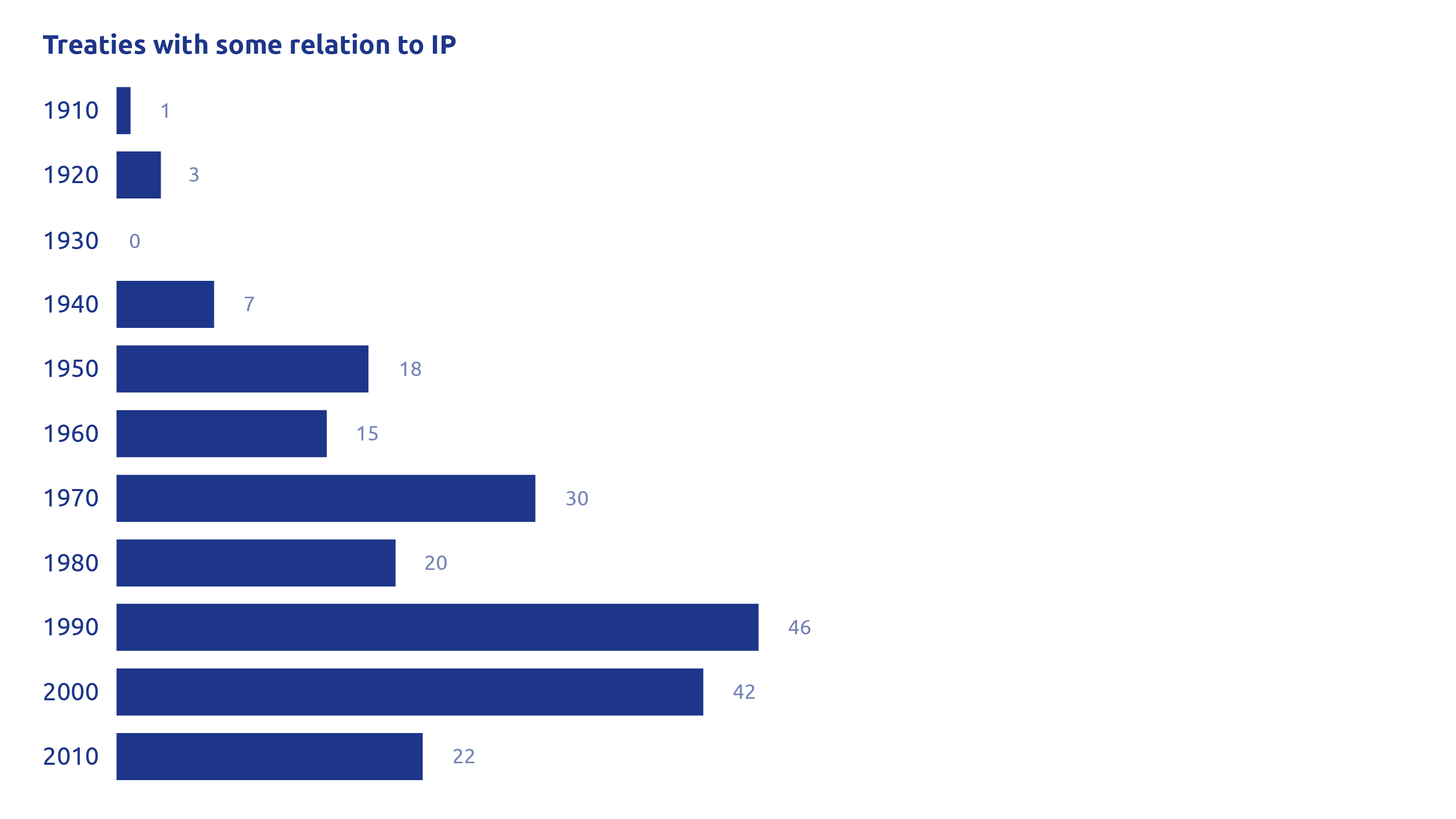

The chart below shows that the growth in the number of treaties was accentuated in recent decades, especially in 1990 and 2000.

Fonte. © Inventa International

This growth is also verified in relation to IP treaties, that is, treaties whose main object is IP. According to the aforementioned WIPO database, these treaties are 77, with 27 having been adopted until 1969 and 50 since 1970. In other words, since 1970 almost twice as many IP treaties were adopted as had been adopted until that date.

Fonte. © Inventa International

The analysis by decade shows that the 2010’s was the one with the highest production of IP treaties, followed by those of 90’s and 70’s. This shows an increasing trend.

Fonte. © Inventa International

Although some of the most important IP treaties are more than a century old, such as the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property (1883), the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, (1886), and the Madrid Agreement Concerning the International Registration of Marks (1891), or almost a century, like the Hague Agreement Concerning the International Registration of Industrial Designs (1925), the intensification of global trade in recent decades has led to the intensification of the approximation of national laws on IP matters and the facilitation of internationalization through new treaties and other supranational sources of Law.

Some of the most important IP treaties have been adopted over the past 50 years. In 1970, the Patent Cooperation Treaty was adopted, with the purpose of, among others, according to its preamble, "simplifying and making it more economical to obtain protection for inventions when requested in several countries." In 1989, the Protocol Relating to the Madrid Agreement Concerning the International Registration of Marks was adopted, aiming to make the Madrid system more flexible and more compatible with the domestic legislation of some countries or intergovernmental organizations that had not been able to access the Agreement. It is this Protocol that currently allows the international registration of trademarks, enabling, with a single application, a trademark to be registered in several countries, reducing procedures and costs. In 1994, the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights was adopted, with the desire to, among others, "reduce distortions and impediments to international trade", recognizing that for this it is necessary to establish "adequate standards and principles concerning the availability, scope and use of trade-related intellectual property rights”.

Evolution also took place at the regional level. In 1973, the European Patent Convention was adopted, which established the European Patent Organization (EPO) and the possibility of obtaining a European patent. Also in Europe, with the European Community, the community trademark and the registered community design emerged, which allowed the protection of marks and product designs in the territory of the now European Union (EU), with just one application and one procedure. In recent decades, EU harmonization laws have made the IP law of Member States very close, and in many respects identical.

In Africa, in 1976 the Lusaka Agreement for the creation of the African Regional Intellectual Property Organization (ARIPO) was adopted, and in 1977 the Bangui Agreement Relating to the Creation of an African Intellectual Property Organization (OAPI) was adopted. In 1994 the Eurasian Patent Convention was adopted, which established the Eurasian Patent Organization (OEAP). In Asia, in 1995 the ASEAN Framework Agreement on Intellectual Property Cooperation was adopted.

New realities and updating IP law

But the changes to IP rules were not exclusively due to the objectives of global and regional harmonization of IP rules and the facilitation of international and regional protection. Other changes, in addition to the intensification of international trade, forced the adaptation of IP law.

The changes were mostly technological. As a general rule, existing IP law is able to provide adequate protection for new technologies. If a patent, a design registration and a copyright can only be attributed to an invention, a design and an artistic work that are new, the novelty is a presupposition of the IP system, so the system is prepared for the innovation because it exists precisely for it. However, the system is prepared for assets like these that are new and not for other kinds of assets. In other words, it is prepared for artistic works, inventions and designs that are new, but it is not prepared for new assets that are not works, inventions and designs.

Computer programs, for example, were one of the main assets that IP law had to come to terms with. However, it was not necessary to create a new right. Software was equated with artistic works and protected by copyright. In situations where they consist of technical inventions, they are cumulatively protected by patent.

"These intellectual assets, not being works, not being inventions, not being distinctive signs of trade, nor being the appearance of a product determined for aesthetic reasons, could not be protected by existing intellectual property rights. The solution, in some countries like Portugal, was the creation of a specific right."

However, new technologies consisted of intellectual assets that could not be equated to assets susceptible to protection by existing IP rights. An example is the topographies of semiconductor products. These intellectual assets, not being works, not being inventions, not being distinctive signs of trade, nor being the appearance of a product determined for aesthetic reasons, could not be protected by existing intellectual property rights. The solution, in some countries like Portugal, was the creation of a specific right.

But technological innovation didn't just result in new intellectual assets that needed protection. Technological innovation resulted, above all, in new ways of using intellectual assets. If television and radio made possible new ways of using works, through broadcasting, the internet did the same, later, but in a more intense and extensive way. In the last decades of these last 50 years, the most important adaptations of the IP rules were due to the use of intellectual assets on the internet. If a company from a particular country sets up an online store using its EU registered trademark, it will, in principle, be using its trademark in any country with access to the online store. If in another country there is the same registered trademark, there will potentially be trademark infringement. The internet has also made it possible to make available to the public works protected by copyright. Consequently, it enabled not only new ways of retribution to copyright holders but also new ways of infringing those rights.

In recent years, it has been mainly the online use of copyrighted works, also a global problem, which has been at the origin of new IP rules. Examples of this are EU directives 2014/26/EU, of 26 February 2014, on “collective management of copyright and related rights and multi-territorial licensing of rights in musical works for online uses in the internal market" and No. 2019/790, of April 17, 2019 "copyright and related rights in the Digital Single Market and amending Directives 96/9/EC and 2001/29/EC", adopted due, according to its preamble, to the "Rapid technological developments [which] continue to transform the way works and other subject matter are created, produced, distributed and exploited”, and by continuing to emerge “new business models and new actors”.

The next 50 years

It is not possible to predict what will happen to the IP in the next 50 years, as the speed of change is increasing. This increase in speed is reflected in IP rules, changing them, and is reflected by the increasing volume of supranational and regional IP rules. With legal scientists increasingly in contact and the legal problems of IP being increasingly global, the trend should be towards accelerating the harmonization of IP rules, although, the some ideological porosity to which this area is subject, may delay that harmonization or even maintain some differences.

Currency Info

Final charges will be made in USD.

Currency conversion is for information purposes only and accuracy is not guaranteed. Overseas customers are encouraged to contact their bank or credit card provider for details on any additional fees these institutions may include for currency conversion.

- USD 312.389 NGN

Territory List

There are no results for your search.

- Africa

- Algeria

- Angola

- Benin

- Botswana

- Burkina Faso

- Burundi

- Cameroon

- Cape Verde

- Central African Republic

- Chad

- Comoros

- Congo (Republic)

- Côte d'Ivoire

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Djibouti

- Egypt

- Equatorial Guinea

- Eritrea

- Eswatini (Swaziland)

- Ethiopia

- Gabon

- Gambia

- Ghana

- Guinea

- Guinea-Bissau

- Kenya

- Lesotho

- Liberia

- Libya

- Madagascar

- Malawi

- Mali

- Mauritania

- Mauritius

- Mayotte

- Morocco

- Mozambique

- Namibia

- Niger

- Nigeria

- Réunion

- Rwanda

- Sao Tome and Principe

- Senegal

- Seychelles

- Sierra Leone

- Somalia

- South Africa

- South Sudan

- Sudan

- Tanzania (mainland)

- Togo

- Tunisia

- Uganda

- Western Sahara

- Zambia

- Zanzibar

- Zimbabwe

- Africa (OAPI)

- Africa (ARIPO)

- Other

- East Timor

- Macao

- Maldives

- Portugal

- European Patent (EPO)

- European Union Trademark (EUTM)

- International Trademark (Madrid System)

- Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT)