Trademarks in Africa – a bird’s eye view on filing strategies

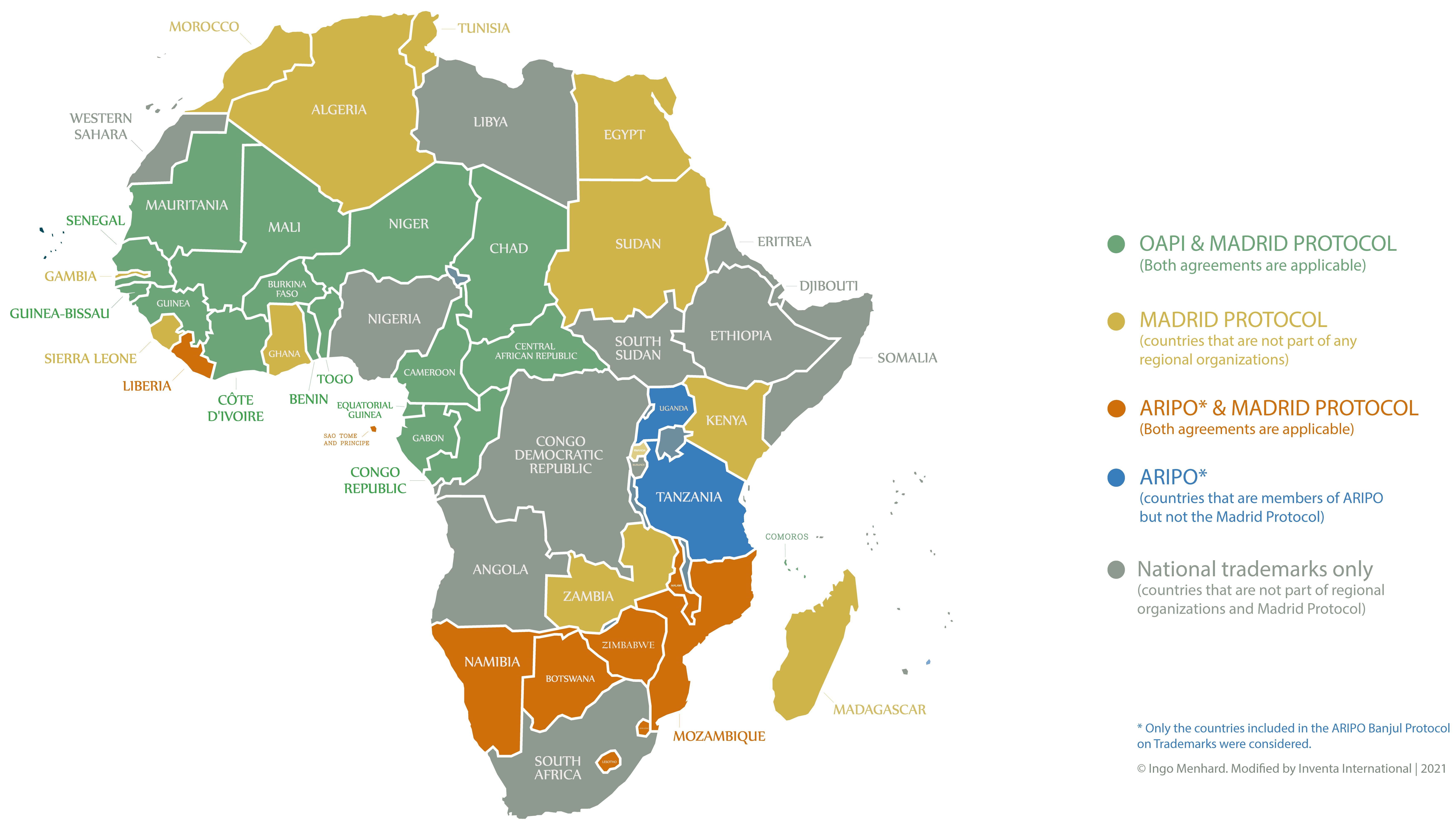

Africa is the continent with the largest number of countries – 54. As trademarks are usually protected at a national level, an African-wide trademark protection strategy can be taxing. However, there are some shortcuts that will help applicants to secure African-wide trademark protection.

Madrid Protocol

The Madrid Protocol for the international registration of trademarks was established in 1989 and provides applicants with the possibility of designating several countries with a single application.

The Madrid Protocol was ratified by 22 African countries, and the geographical reach is extended to 38, due to the participation of the African Intellectual Property Organization (OAPI). Putting this into perspective, about 2/3 of the continent are covered by the Madrid Union, allowing applicants to take full advantage of the system and obtain cost-effective protection throughout the continent. There are some notable exceptions of countries that did not join the Madrid Union, such as Angola, Ethiopia, Nigeria, South Africa or Tanzania.

For the most part, it is possible to circumvent the need to contact national trademark offices. However, there are some circumstances where the Madrid Protocol might not be the best option for applicants.

First, there are local challenges that make it difficult to ascertain if a trademark was indeed granted and if it is enforceable under national law. Several member-states do not issue statements of grant of protection, as a result of larger backlogs, undigitized records or delays in the administrative proceedings due to office actions or oppositions.

While Article 5 of the Madrid Protocol provides that countries can only issue notifications of refusal within 12/18 months after the notification of extension, potential conflicts between national and international law arising from the above-mentioned reasons do not provide applicants with the sufficient legal certainty to ensure that their trademarks – beyond a reasonable doubt – are locally enforceable.

Second, there are several countries that did not enact domestic provisions to apply the Madrid Protocol. In countries with a Civil Law tradition (mostly Arabic, French or Portuguese speaking countries), implementing regulations is a necessity depending on the constitutional norms that directly apply international treaties or as a practical need to ensure that the administrative proceedings correctly handle international trademarks. In countries with a system of Common Law, the incorporation of international law is usually required to ensure that their provisions are legally binding in domestic law.

Third, while the regional organization OAPI fully implements the Madrid Protocol and examines international applications, there are substantiated questions about the enforceability of international trademarks that designate OAPI. OAPI’s Bangui Agreement does not explicitly mention the Madrid Protocol in its procedural provisions, and it is unclear whether the regional organization has the legal powers to ratify international treaties on behalf of its member-states and not merely implementing them.

As such, applicants should be aware of these difficulties when filing international applications in Botswana, eSwatini, Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Malawi, Namibia, OAPI and its 17 member states, São Tomé e Príncipe, Sierra Leone, Tunisia, Zambia and Zimbabwe. On the other hand, international trademark applications are advisable in Algeria, Egypt, Madagascar, Morocco, Mozambique, Rwanda, Sudan.

Finally, while the above considerations and legal uncertainties can be more theoretical than practical, they are yet to be tested before national courts of law. As IP litigation in Africa is still sporadic it can be difficult to provide much needed clarity regarding the enforceability of trademarks, especially for applicants with greater concerns in anticounterfeiting.

OAPI

The African Intellectual Property Organization was established in 1977 by the Bangui Agreement and created a regional trademark system in West and Central Africa, mostly comprised by French speaking countries.

OAPI currently has 17 member-states, namely Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Chad, Comoro Islands, Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Senegal and Togo.

The main advantage of this regional organization is that it allows applicants to submit a single trademark application that automatically covers all its member-states. In fact, the system is unitary in the sense that trademarks are valid in all countries without the possibility of individually designating specific countries, in a similar fashion to Benelux or European Union Trademark systems.

Furthermore, the Bangui Agreement functions as a national Intellectual Property Code, especially because its member-states do not have national IP legislation. However, enforcement actions still need to be handled at a national level.

It should be noted that separate applications for goods and services have to be filed. The usual timeframe for filing up to registration is 10 to 14 months, including a 6-month post-grant opposition period. Trademarks are valid for 10 years from the application date and renewable for further periods of 10 years.

ARIPO

The African Regional Intellectual Property Office (ARIPO) was established in 1976 by the Lusaka Agreement and further capacitated by successive Protocols, such as 1993’s Banjul Protocol on Marks, mostly comprised by English speaking countries.

Of ARIPO’s 19 member-states, 11 became parties to the Banjul Protocol on Marks, namely Botswana, Eswatini, Lesotho, Liberia, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Sao Tome and Principe, Tanzania, Uganda and Zimbabwe. Zanzibar has a separate registration system from mainland Tanzania and is not included with ARIPO designations.

Under ARIPO’s registration system, applicants are able to file a single trademark application, designating the above-mentioned countries. After a formal examination, the process is forwarded to each country’s IP Office to conduct separate examinations, according to the applicable national provisions.

Unlike OAPI, ARIPO applications do not automatically cover all member-states and do not have a unitary effect, so it is possible to secure registration in regard to some of the designated countries. In this sense, ARIPO’s system is more similar to the international system implemented under the Madrid Protocol, but still has the advantage of allowing applicants to centralize most proceedings before ARIPO’s bureau and not individually with each country’s IP Office.

The process from application up to granting can take between 12 to 18 months, including a 3-month opposition period. Trademarks are valid for 10 years and are renewable for successive periods of 10 years.

While ARIPO is not party to the Madrid Protocol, its member-states individually joined the international system, with the exception of Tanzania and Uganda.

Concluding remarks

While filing international trademarks in Africa can initially sound like a daunting process considering the sheer number of jurisdictions, using the Madrid Protocol and the two regional IP organizations – OAPI and ARIPO – provides applicants with much desirable shortcuts to secure broad territorial protection.

Applicants should be aware of the advantages and shortcomings when deciding to use the Madrid Protocol, OAPI or ARIPO, so that their registered trademarks are not hollow rights and are able to be locally enforced before courts of law.

This article was originally published in The Trademark Lawyer (Issue 2 - 2021)

Lista de Territórios

Não existem resultados para a sua pesquisa.

- África

- África do Sul

- Angola

- Argélia

- Benin

- Botsuana

- Burkina Faso

- Burundi

- Cabo Verde

- Camarões

- Chade

- Comores

- Costa do Marfim

- Djibuti

- Egito

- Eritreia

- Eswatini (Suazilândia)

- Etiópia

- Gabão

- Gâmbia

- Gana

- Guiné

- Guiné-Bissau

- Guiné-Equatorial

- Lesoto

- Libéria

- Libia

- Madagáscar

- Maiote

- Malaui

- Máli

- Marrocos

- Maurícias

- Mauritânia

- Moçambique

- Namíbia

- Níger

- Nigéria

- Quénia

- República Centro-Africana

- República Democrática do Congo

- República do Congo

- Reunião

- Ruanda

- Saara Ocidental

- São Tomé e Principe

- Seicheles

- Senegal

- Serra Leoa

- Somália

- Sudão

- Sudão do Sul

- Tanzânia

- Togo

- Tunísia

- Uganda

- Zâmbia

- Zanzibar

- Zimbábue

- África (OAPI)

- África (ARIPO)

- Mais Territórios

- Macau

- Maldivas

- Portugal

- Timor Leste

- Marca da União Europeia (EUIPO)

- Marca Internacional (Sistema de Madrid)

- Patente Europeia (IEP)

- Tratado de Cooperação em matéria de Patentes (PCT)